In Search of James Lavelle: A Herb Sundays Mo' Wax Sunday Edition

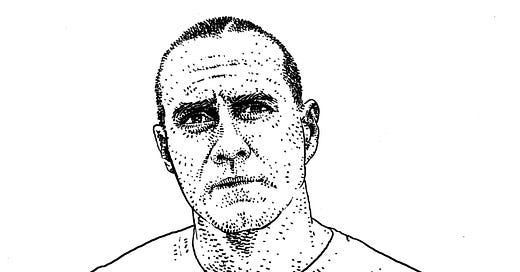

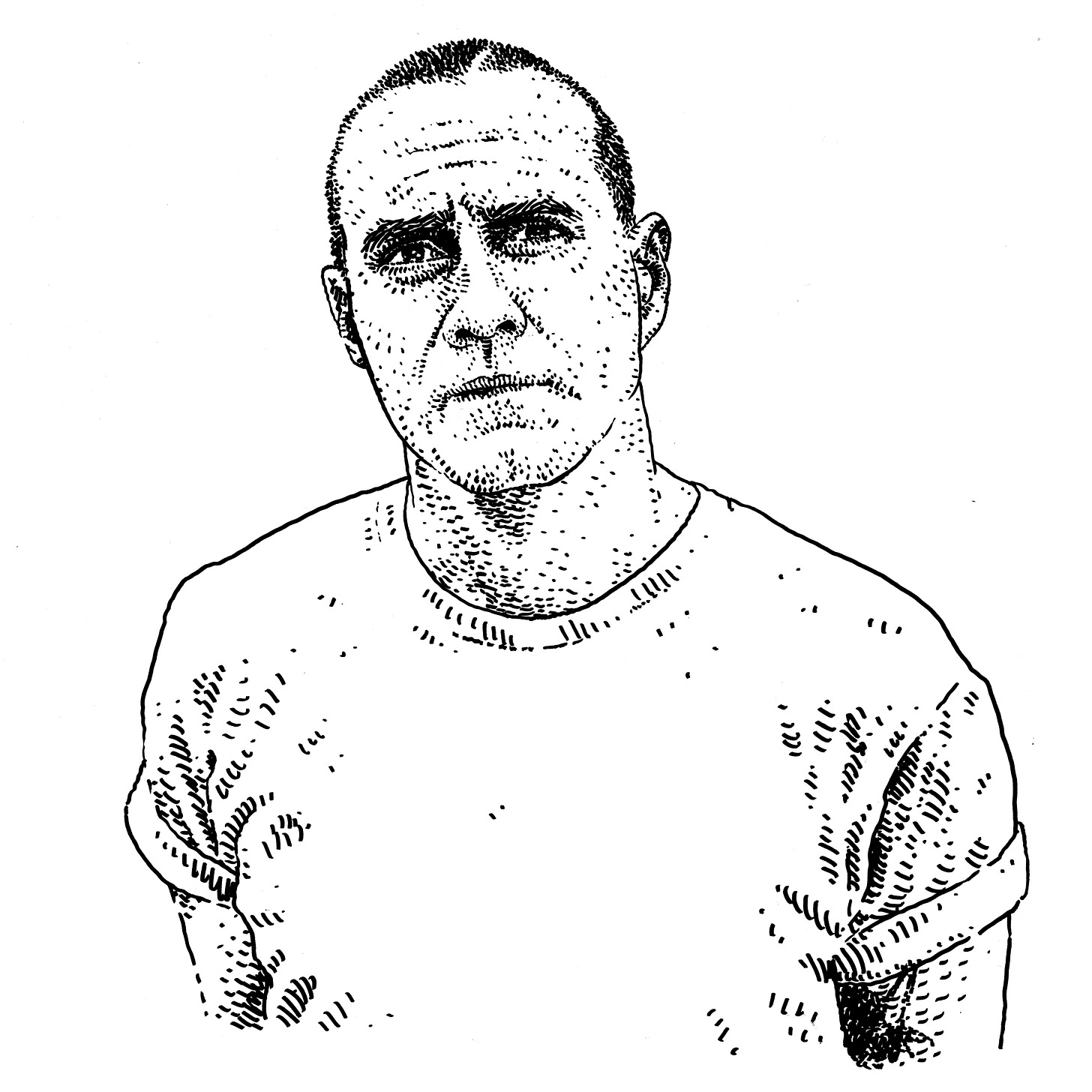

A Herb-That-Didn't-Happen™ by Sam Valenti IV. Playlist by Rob Sevier of The Numero Group. Art by Adam Villacin.

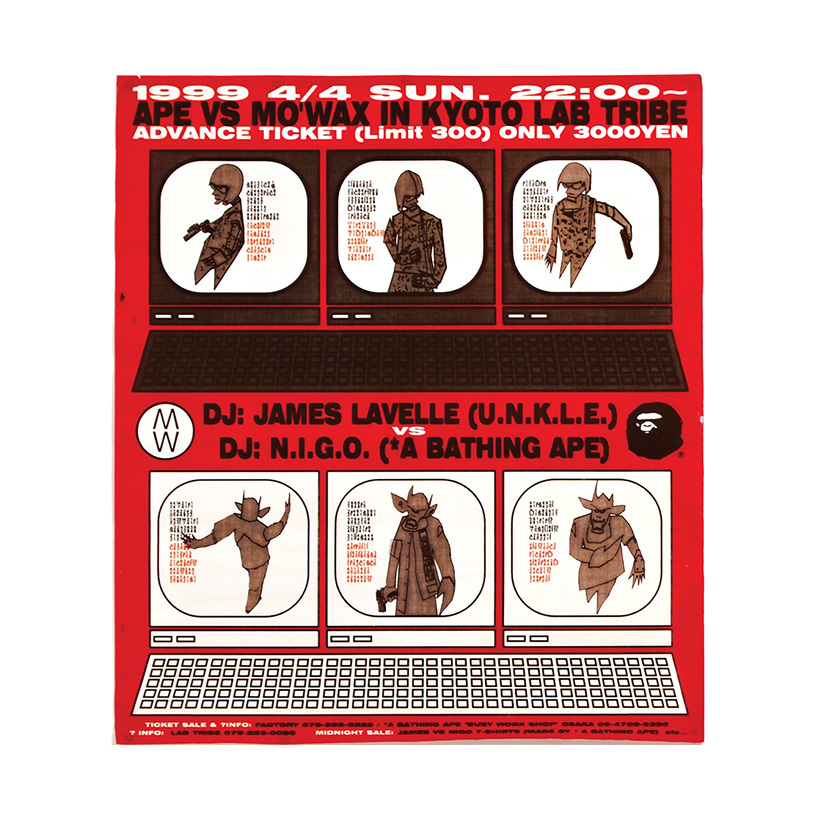

“There is a sharp intelligence that he hides behind the slang and jargon of the perpetual teenager. And he turned being a perpetual teenager into a successful career. Lavelle did everything. He was a DJ, scene-leader, producer, record company executive–but primarily, an effortless networker whose connections spread across the world. He got to know the Beastie Boys and graffiti artist Futura 2000 (who did his tattoos) in New York. In Tokyo he connected with designer Nigo of the clothing label A Bathing Ape and the act Major Force. He befriended Massive Attack in Bristol. He hung out with Oasis and talked Thom Yorke and Jarvis Cocker into guesting on his albums. Mo’ Wax became a byword for a certain cool–a global boy’s bedroom, filled with all the things James loved. There were his records, his Star Wars posters, his rare toys, his trainers. But Mo’ Wax was also a creative centre, an axis in that crazy mixed-up world, a Factory Records of the 1990s. ‘You had intellectual, working class, everyone was hanging out and everyone just wanted to do these crazy things,’ said Lavelle. And for a minute, it seemed anything was possible.’” - Dom Phillips (1964-2022), Superstar DJs Here We Go!: The Rise and Fall of the Superstar DJ

This is the story of a Herb Sundays that didn’t happen, like the KLF one before it.

But we have a soundtrack. I asked my friend Rob Sevier of The Numero Group (a fellow Secretly Affiliate label), a Mo’ Wax enthusiast and DJ Shadow compatriot, to share some faves. Due to rights issues, many songs aren’t available and original albums and artwork don’t appear, but close your eyes and imagine. He compiled them below in true Headz fashion, so read on for the proper list a the bottom, but here’s the mix up top (Apple Music, Spotify). When you hear the beep, turn the page….

London, January 2024

At the top of this year, I must have felt ambitious, more ambitious than I do right now. While in London, I tried my luck at reaching Mr. Bill Drummond for a Herb Sundays entry (again, a fool’s errand I know), I also reached out to James Lavelle, one of my boyhood heroes to see if we could meet up. I already had emails into him asking for a mix, but this felt different. He agreed, and we met up on a cloudy Saturday to chat.

London, July 1999

I’m standing outside a club, which one I can’t remember. It may have been Bar Rumba to see James Lavelle and Gilles Peterson do their seminal That’s How It Is club night (1992-2005), which has a fabulous playlist by Lavelle), or it was more likely at the newly opened Fabric. Lavelle is walking in or out, I can’t remember. I stop him and hand him the first release on my record label, a 12” by Matthew Dear which he graciously accepts. I sheepishly asked if I can reach out to him while I was in town. I produced the only paper I had, a blue Paris subway ticket (I have it somewhere) and, luckily, a pen. He writes his number on it and goes on his way.

Lavelle is only about five years older than me but it all felt, and still feels, like a whole different generation. As a teen in the late ‘90s, I inhaled everything I could find on Mo’ Wax and for rare transmissions from Toyko and London in a pre-mass internet age, mainly the places Lavelle seemed to be all at once. As a Hip-Hop fan, the label felt like an atlas of related scenes, connecting dots between Drum & Bass, Techno, and of course something all it’s own. It was intoxicating stuff. The only time I ever dyed my hair was in a little blonde strip, trying to look like Lavelle. He, the one who started the world-conquering label at only 18. Well I was trying to do it too.

I arrived before him for our Jaunary meet and he comes in wearing the customary Major Force bomber jacket with the slightest Mohawk (he has to go off to get a haircut, so can’t stay long), and he’s still the guy. We had a fabulous talk, deeply fulfilling stuff but the requested playlist never arrived. I don’t fault him, he is busy at the moment, and said as much up front, so I harbor no ill will. 25 years on and I’m still hunting the guy.

I still had to get this writing out though, for myself. Making sense of all this stuff. In reviewing all things Lavelle including the Mo’ Wax book, documentary, and various clips recently, I’m struck by how different Lavelle can look, which is a great metaphor for his personality. In old clips, he’s often the wiry geek with the thick glasses in his BAPE tees and big pants, and then sometimes he’s a jock or the bully, maybe not dissimilar to James Murphy, another Peter Pan ambivert, the nerdy kids set loose in the cockpit of culture.

Being a child of Mo’ Wax was cool for a moment, but as we got deeper into the 2000s; it was seen as well, Herby. I, and culture, had moved on so to speak. But I never let the flame die entirely.

Culture feels ready for another run though. Trip-Hop, the love-or-hate genre name, is starting to creep back into the sonic vernacular with dusty breakbeats feeling like comfort food after a long time away. Lavelle, perpetually 10 years ahead of the culture, celebrated his fabulous Rizzoli book and Meltdown festival a decade ago, but it feels like the war on Trip-Hop, and a re-appreciation of DJ Shadow’s masterful Endtroducing… at 25 years (with a Zane Lowe interview to boot), is upon us.

Lavelle cast his crew as a hub between London, Tokyo, Los Angeles and beyond, forming a wave of projects by a generation of kids who grew up on surf, skate, and hip-hop like Shawn Stussy and James Jebbia (Supreme). As a DJ and record clerk, Lavelle felt the ground moving beneath him so the story of Mo’ Wax is about the convergence of many things, so Lavelle, as a keen scout of people and ideas, was keen to pick up on. From the eclecticism and knowledge-based elitism of revered record shops like Honest Jon’s to the import savvy of Slam City Skates (both still operational) to the International Stüssy Tribe concept, Gen X was forming culture in its own image. Trip-Hop (a name from the mind of Mixmag’s Andy Pemberton) was and is painful to say, but it worked, canvassing a global network of artists as a unified aesthetic. As a Wild Bunch/Massive Attack acolyte, Lavelle was near the fire at an amazing moment in time, competing for the signing of groups like Portishead and Tricky, and apparently Hip-Hop acts like Organized Konfusion and Company Flow, all while launching a barrage of shoe and toy collaborations, countless remixes (Plastikman, Autechre, Carl Craig), global events, and gigs with unbelievable velocity.

For context, I asked culture academic and writer W. David Marx (Herb 53) for his thoughts. Marx, an American-born Bathing Ape historian, NIGO insider, and Tokyo denizen, has the perfect perch to give me his Lavelle take:

Looking back from today, when Pharrell Williams is the menswear creative director at Louis Vuitton and K-Pop stars wear clothes from the Japanese designer NIGO, James Lavelle only feels more historically important. He emerged in the London music scene with acid jazz and then trip-hop, working alongside his friends and colleagues at Stüssy and adjacent streetwear companies like Gimme Five. He went to Japan very early with the magazine Straight No Chaser, where he met NIGO of the brand A Bathing Ape. They became a cultural power duo for the next decade, and between Lavelle's label Mo Wax and NIGO at Bape, they created the playbook of how to combine underground music with graffiti art, wild graphic design, and commercial savvy into an aesthetic visual universe. In those days, it was all for the heads in London, New York, and Tokyo — now it's for nearly everyone.

Indeed, Lavelle’s everyday movements now seem commonplace. “Merch” dominated the last decade, as fashion and music are now considered part and parcel. There are a lot of gestures that Lavelle helped inform and innovate on: The pairing of dance and rock music (like DFA after it, which UNKLE producer Tim Goldsworthy co-founded), ornate reissues with new artwork (see: Mo' Wax’s take on Liquid Liquid), Concept/post-human bands (UNKLE begets Gorillaz, perhaps), Non-technical producers/producers as “vibe chiefs” and/or resurrecting careers (Lavelle with David Axelrod, Rick Rubin’s work with Johnny Cash), Toys as Art (preceding the Kid Robot era), and perhaps most importantly, globalism and diversity as core tenets, as opposed to regionalism. The list goes on.

The real thing that Lavelle was early on, which he gently reminded me of when I asked him if he had any regrets or misconceptions around him, was the one that cost him his crown, perhaps. The thing was that it wasn’t cool to be too successful. Lavelle wanted very badly to be, and whether it’s the perils of the UK PR machine or just Gen X’s fear of selling out, this was the most damning thing perhaps, a problem which NIGO didn’t have to bear, or more behind-the-scenes types like Jebbia, moves which now would be seen as essential for culture-making. What a difference a decade makes.

To re-frame Mo’ Wax as I’ve done internally, instead of as a failure or one guy’s thing, it feels better to think of it more along the lines of all great culture brands, which are indeed a group of incredible artists and creatives (and their fans) marshaled by visionary leadership. In a faraway sense, Apple is increasingly becoming this, less about Steve Jobs and more about the myriad voices that made Apple great, i.e., this Susan Kare interview that is making the rounds in my group chats. Great movements are indeed the sum of a lot of people and their work, but you also need pushy people like Lavelle to help move it along.

The school of Mo’ Wax indeed begat a generation. The visuals department alone bears noting: Futura is about to open a Bronx Museum retrospective, the cap on a late-career renaissance that has made his work ubiquitous, the most famous of all the original NYC graffiti writers. I would argue that without Lavelle/UNKLE, there would have been a huge gap in time where awareness of Lenny’s brilliance may have been unheralded.

Then there’s the great Ben Drury, one of the most talented commercial graphic designers ever born, and Will Bankhead who runs the peerless The Trilogy Tapes label and brand, seamlessly integrating product and music, like his alma mater. Toby Feltwell (Herb 20), who spent time at XL and Bathing Ape, co-founded the beloved Japan-based clothing label Cav Empt, which also throws events and releases tapes.

I’m not printing the interview because it was meant to accompany the mix, and it doesn’t feel right to do so without it, or his final word but we covered a lot of ground in our convo. While Psyence Fiction isn’t my favorite Mo’ Wax project by a long shot, I mentioned my love for “Guns Blazing” and the inclusion of Kool G. Rap which opens the album, something which he gives Shadow credit/blame, that having a heavy song like that up front probably cost a lot of sales for HMV/Tower record shop listeners checking out the CD on in-store headphones and not hearing a “chill out” record. He’s not wrong.

There’s a lot of what could have been in the Mo’ Wax story, but with distance, it was a complete run and a success, as most pioneering labels don’t last that long. If looking at UK archetypes like Factory (1978-1992) and Creation Records (1983-1999), then Mo’ Wax (1992-2002) was actually a complete arc. Hundreds of projects exist, many of them great, and many just promising, but that’s the odds for any label or creative endeavor. There are many good Web 1.0 sites to plow through, but I’d start with Mo’ Wax historian James Gaunt who chronicles many of these unfinished projects in his myriad posts. Lavelle also got the memo that dance clubs were where the action was and positioned himself in a new era of globetrotting DJs in a more dance music sense. He was already a resident at Fabric and the chosen name to start their new CD series. He was moving on too. Endtroducing… not Lavelle’s album, but one only he could have midwifed to a major label, had already changed the world. It was done.

While it’s easy to deride Lavelle for his inability to hold it together longer, we must remember the soil on which Mo’ Wax was built, Fin de Siècle London was (and is) very patriarchal, very old guard. In his estimation, Lavelle represented “geek” culture (which included the insurgent Radiohead), which was at odds with the dominant “lad” culture (his words). The way I interpret James’ experience of the music industry at the time of Mo’ Wax was (through my Disney prism, of course) Pleasure Island and The Stupid Little Boys of the scene all found themselves victims to the primary vices of the time, thus making Lavelle the sensitive Pinocchio in my parable.

Indeed, a Lavelle of now would be allowed to go home early, encouraged to store up his energy. Not so of this era. The main phantom in the Lavelle story is excess (read: drugs), which he admits, and while he was an adult, he was only barely. The music scene, especially the dominant rock culture (which was also brit-pop and supermodel culture) that Lavelle sought acceptance in, was heavily addled, and any chatter about mental health or anxiety would have been seen as weakness, a charge he probably couldn’t have faced. Very few were looking out for him he feels. At 50 years old, Avicii’s death haunts Lavelle as a close call, as does Keith Flint’s as a contemporary figure. There are a lot of haunted corners and near misses in this orbit.

I had walked the Hip-Hop sale at the Upper East Side Sotheby’s building in the summer of 2023, peering at the Futura 2000 originals Lavelle had purchased to use as cover art. Sitting still as soldiers, they still astound. They are still firmly from the future. So much of this oeuvre still hits, especially the small stuff. See the unreleased Lego concept alone.

As I left our meeting location in Soho, I coincidentally walked by London’s Supreme outpost. In the staircase hangs a giant Mark Gonzalez sculpture, an artist Lavelle had made toys for many years ago. Stark and clean like an Apple Store, the Supreme shop, a brand I adore for its past successes and discipline, and one that comes from the same ‘90s brat pack as Mo’ Wax, has now been sold twice for billions. This is the world Lavelle helped birth, which is a bit hard to stomach, but It’s also hard to imagine the irascible Lavelle being able to last through the necessary corporate pains to achieve this scale, he may have found similar frustrations like he did at the major labels. He’s not a guy to be cornered.

The kids and tourists lined up like in any other city, dead-eyed and seemingly joyless, “bathing in lukewarm water” as NIGO would say. We’re all just consumers now, I couldn’t help but think, looking for a taste of the genuine artifact. Lavelle was one of the adventurers who helped bring it all home, a Fitzcarraldo of the limited edition, the rare, the colorful, the bold. So, in the spirit of Herb Sundays, flowers are due, even with a little ribbing here and there. We salute Lavelle and the cadre of global artists he helped embolden.

A Head’s Headz Topography

I asked Rob Sevier for his Mo’ Wax faves, which are listed here in his own words:

Mo’Wax Top 5 LPs:

DJ Krush - Strictly Turntablized: a perfect exercise in minimalist, angular downtempo, the blueprint for lofi study beats but sadly absent on the streaming services where this sound has exploded

Luke Vibert - Big Soup: more like maximalist downtempo, pastiche without being kitsch

DJ Shadow - Endtroducing: while Mo’Wax seemed intent on defining a new sound, it turns out Endtroducing would do that more or less on its own. The biggest and best release on the label by any metric

Parsley Sound - Parsley Sounds: the latter version of Mo’Wax, with a different and arguably much worse visual sensibility. A twee album cover hides a visionary bit of proto-Salvia Palth (or Steve Lacy)

Urban Tribe - Collapse Of Modern Culture: came to this record years after release as a Moodymann oddity, but it is a visionary fusion of Detroit sounds managing to scoop up bits of techno, house, ghetto tech, bass, and insert them into an abstract downtempo, proto-west london house context

Mo’Wax Top 5 12”s:

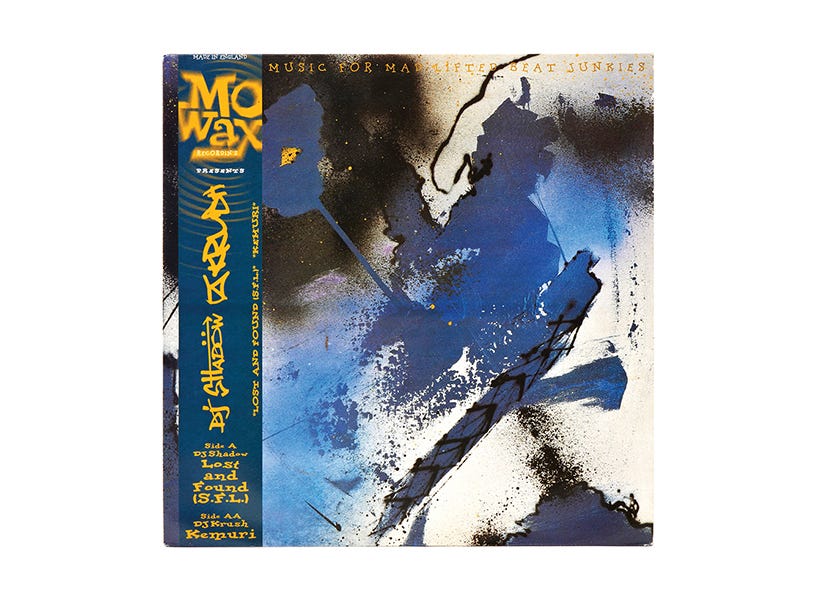

Headz 2 Sampler: Zimbabwe Legit (Shadow’s Legitimate Mix) and DJ Krush “Kemuri”

DJ Krush “Meiso” - specifically for the Klub Mix by DJ Shadow

DJ Shadow - Influx

Attica Blues - Vibes Scribes & Dusty 45s

La Funk Mob - Tribulations Extra Sensorielles

Top 5 Reissues

Air - Modulor: i never even saw the Source Lab edition in a shop… this cover strips away the kitsch and made it not just a synth novelty

Dr. Octagon - Dr. Octagonecologist - issued first by The Automator’s Bulk label, the Mo’Wax edition wins for both art & packaging [Sam’s note: I veer from Rob’s take here, perferring the Pushead illustration of the original cover, all pulpy and wonderful.]

Blackalicious - Melodica: even just adding the instrumentals on disk 2 made the mo’wax edition essential

Now Thing (Various) - this is the last gasp for Mo’Wax as far as I can tell, and it took me by surprise when i flipped this strange looking record over to see a Mo’Wax logo [Sam’s note: curated by Toby Feltwell!)

Shadow/Chief Xcel - Hardcore (Instrumental) Hip-Hop/Fully Charged On Planet X: again Mo’Wax wins by matching style with substance

Best Compilation:

Headz 2B: There are an abundance of compilations on Mo’Wax. I’ve listened to all of them… it’s a tough call between a few, but the Heads 2A and 2B comps check boxes for packaging, curation, original content, and interludes from The Prunes that really tie it together. If there’s a fire and i can only grab one of these weighty boxes, i’m going 2B

I think about (and listen to reconstructions of) those Headz 2 compilations all the time. A bummer the Mo' Wax thing isn't remembered more than it is. Thanks for this.

The point about convergence is key imo. That vision and will to create a blockbuster-like universe around the music he loved. The artwork, the characters, the streetwear, the toys...

I've always admired James' hustle above all else. I still remember interning at Straight No Chaser and Paul Bradshaw telling me this story about some kid from Oxford who bowled up at the mag's East London office and declared, "You need me".