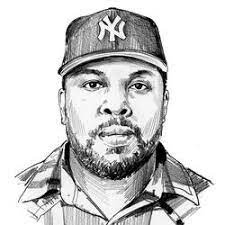

Herb Sundays 84: Craig Jenkins

The New York Magazine music writer with a dynamic megamix for both the lost and emerging heroes

Herb Sundays 84: Craig Jenkins (Apple, Spotify, Tidal, Amazon). Art by Michael Cina.

“This year I've been: missing the dead homies, watching casual cruelty infect everything, learning boatloads about sound synthesis, and retreating into fictitious worlds where teenagers and massive robots solve all the problems.” - Craig Jenkins

Craig Jenkins grew up in New York City as a band geek with an interest in writing that took center stage when he “flaked on practicing instruments.” He rode the school newspaper-to-blogspot-to-Tumblr pipeline, catching the attention of editors which would lead him to freelance at outlets such as Pitchfork, Complex, Spin, and Billboard, and then as a writer/editor at Noisey. He started his first staff job in 2016 at

and Vulture, which Herbheads know I ride for (see Allison P. Davis’s Herb 57). His continuing work there made him a Pulitzer finalist for criticism in 2021.Like an action movie hero you can drop into any situation, Jenkins is comfortable with all sizes and stripes of musicians and can be trusted with an interview in any scene. He’s what Herb 53 W. David Marx would call “omnivorous” but instead of condescending or shallow, he gets the nuances of various genres in a way most people can’t. Jenkins is on his nerd shit too as a evidenced by his recent spray of tweets on the new Zelda game. He’s a perfect critic for modern fandom with a need for S teir references. A new Janelle Monáe review, for instance, references Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam, Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, and Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot.

The playlist is a 69 song, 4 hour and 20 minute affair (!) and lest you think this is a camera roll dump of tunes from his faves list, I watched Jenkins tweak this more than a few times. The mix has some major themes: The lost ones (Belafonte, Melvin Van Peebles, Mac Miller, Linkin Park, Alice Coltrane, Sakamoto, Tina Turner, De La Soul, Doom as Geedorah), some fin de siècle fizzy electronics (Goldie, Ultramarine, the punchy “Tesko Suicide” from Sneaker Pimps, Stereolab, Mu-ziq x Aphex), and the contemporary up and comers (Liv.e, billy woods, Yachty, Nilüfer Yanya, UMO, Steve Lacy, Arca).

Jenkins was a writer I’ve always slowed down to read, as his style is straightforward but with a lot of emotion underneath. I had never heard Jenkins speak so when I checked the the “Enjoy The Silence” episode of Herb 49 Rob Harvilla’s 60 Songs That Explain The ‘90s podcast and he talked about how the Violator album is sort of knocking at the door of Hip-Hop (a bugged out idea I had never thought of), I knew I had to reach out.

His 50+ reviews at Pitchfork chronicled the rise of a new wave of star MCs in the ‘10s including Kendrick, J. Cole, Migos, Vince Staples, etc. and his hit rate for good takes was exceedingly high. Jenkins and Pitchfork’s editors new that If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late was perhaps Drake’s high point disguised as a low point. Jenkins handily explains:

Whether the Drake tape is a clever track dump disguised as an album with the intent of worming out of his Cash Money deal, a deliberately planned gesture to tide fans over until the upcoming Views from the 6, or just an exercise in shirking the protracted waits and missed dates of the retail rap game, If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late winningly employs the occasion of the So Far Gone anniversary to revisit the twilight consternation of Drake’s breakout release, perhaps to close out a chapter of his career on the same note on which it began.

He’s great with the underdogs (“session work is rewarding but also nomadic and sometimes frustratingly anonymous…Their names are known only to bands, industry hawks, and intrepid diehards who comb album credits (insofar as these names ever make it into the credits.”) and his love of music is not didactic, he sees it all. It’s prob not fair to quote something from a decade ago but this pull from his 2013 My Year In Music from Pitchfork warmed my Herby heart (He then goes on to extoll the virtues of Daryl Hall and Prog Rock):

Musical Lowlights: “Didactic pop. Carnivorous pop. Pop that tells you that other pop isn’t good for you. "Royals". "Thrift Shop". "Hard Out Here". Any song that felt charged with telling the listener, "Hey, these other songs are doing you all a grave disservice with their gross materialism and unrealistic premiums placed on looks and belongings. But we’re all just regular people here, and there’s a beauty in that. And I’m here to appraise it for you." Fuck that message. Pop is escapism as much as it’s realism.”

Life, Death and Hip-Hop

Craig Jenkins is pissed. The great ones keep dying and he can’t keep up. Jenkins is good at obituary luckily (along with Herbfriend writer Jeff Weiss who is also deft) and he continues to try to beat this feeling, and the subsequent futile late praise, to the punch. On A Tribe Called Quest:

“As kids, we think the things we love are built to last. Parents are immortals. Heroes are unflappable demigods. The end of innocence arrives when we learn otherwise — when death tosses a mean fastball that shatters our defenses. The pitches are coming too quickly lately. I am writing more eulogies and remembrances than I ever believed I could. I am subsisting off of memories more than I thought I ever would.”

Herb Sundays itself is sort of a “pre-death obit” blog in itself, a Tumblr idea I had a while back that wormed its way into this concept. The idea to me is not morbid, its more positive, taking the thoughts you have uncollected and putting them out now. After the death of an artist things change, circles close, and the temerity of statements increases but also decreases too. Humor and critique is often lost.

Jenkins loves his musical heroes, and the pain they endure for us. The great George Michael is “a modern pop St. Sebastian. He tried to show us how to loosen up. We weren’t ready.” MF Doom was was a villain because society and the industry made him one (“So as we mourn the man, it behooves us to speak not just to his greatness but also to the closed-mindedness and cruelty that complicated his life and necessitated his dark turn. The villain made do; let’s stop making villains.”)

He can boil it down quickly as in an obit for Prodigy of Mobb Deep.

I believe that rappers know something the rest of us don’t. They think and work too quickly. They rise and fall too sharply. They see too many sides of too many different people. They’re frequently wise beyond their years and, almost uniformly, delightfully strange, as anyone lucky enough to gain an audience with one would attest. It’s as if they’ve been presented with a cheat code to the natural systems of life.

Mac Miller popped up on the playlist and I quickly revisited Jenkins’ feature on Mac who Jenkins rightfully saw as a friend, published just day before Miller’s death. The link to the piece remains Jenkins’ pinned tweet.

I relate, and I always convince myself that other people who strike me as having had to work through hardships like anxiety and depression are built to last. I fall clean and hard when things turn out differently.

Follow up: My Definition of Sleaze House

Thanks for the kind feedback (and pushback) on Herb 83 from The Dare. As does usually happen, I end up swimming in the music and themes of the previous week’s Herb a bit and found myself revisiting some of the early ‘00s Electro (no -clash) and that informed me at the time and made a little bonus mix (Apple, Spotify).

One song pulled me back in particular, “You And Us” (2001) by Miss Kittin & The Hacker, or a travelogue in song form. While most ‘80s M/F duos were "fire and ice" with big female vocals on icy synths, K&H update the formula where the Hacker's beats provide the warmheartedness with big chromatic Italo Disco chords in contrast to Kittin’s monotone. It's no less sinister though, all 303 bassline and overdriven drum computer. Kittin is hot mic'd, not sampled or “punched in" to the track. All the better to deliver one of the most perfect odes to the Techno life, a hostel-dwelling update on "Autobahn."

The lyrics describe a weekend of gigging, leaving their native Grenoble for some imaginary town to share their wares. When The Hacker pops the clutch and opens the hi-hats at 1:30 it's off to the races. The majesty of the French countryside whizzing by, it's the Eurostar dream, far before Easyjet Techno. Hop a train with a box of records and a friend, change your life forever.

I thought more about the era and realized “Electroclash” was a bid for celebrity in the pre-smart phone world, a way to make DIY feel exciting and prosperous, but also a send up of the nascent Paris Hilton effect. Through a modern lens it looks thirsty, but it was subversive to play these games at the time. I forgot that the faces of the -Clash world, Fischerspooner, were actually a downtown art world fixture, cavorting with Gavin Brown, etc. “We really tried to dive in head first into this empty swimming pool that is the space between art and entertainment, pop culture and 'high' culture, and to try and make something meaningful and lasting.”

In an interview with Nick Catucci (who co-runs the very good Embedded Substack now) for Vulture, Casey Spooner opines:

Early on, you were associated with the electroclash scene—

I don’t know what you’re talking about.Is there a cohesive group of musicians that you feel you belong with now?

I don’t know. I just look at that period as such a moment. Everyone was so terrified of Y2K. If I’m gonna die at the strike of midnight, and the whole infrastructure of the entire Western Hemisphere is going to implode, I’m going to be dancing in a motherfucking jockstrap to bad dance music, covered in sweat and glitter.