Herb Sundays 138: Gary Hustwit [on Eno]

The documentary filmmaker (Eno, Rams, Helvetica) explores the Brian Eno canon.

Herb Sundays 138: Gary Hustwit (Apple, Spotify) [Season 9 premiere]

Art by Michael Cina.

“Brian Eno is probably the most prolific artist I've ever encountered. He's been actively making music for over 54 years now, has released over 40 solo and collaboration albums, and produced dozens more. Stylistically his output has varied wildly, from glam rock to his early ambient records to Bowie to his recent collaborations with Fred Again.. So trying to pick any subset of Eno and Eno-adjacent music is really challenging. I decided to be hyper-specific and went with a Sunday morning vibe with these picks, starting out ambient-ish and then getting a little more rhythmic before dissolving into light with Laraaji.

On one level I'm almost too close to his music after six years of intensive work on the film. But even after all that, I still get surprised by certain songs if I start digging into his catalog. Like the wonderfully titled 2011 collaboration with Rick Holland "As If Your Eyes Were Partly Closed As If You Honed the Swirl Within Them and Offered Me the World". Or "A Different Kind of Blue" from the 1995 album by Passengers (a collective pseudonym for Eno and U2). What's mind-blowing is that Brian is still in his recording studio every day making new music. I hope we can all stay as curious as he's been for the past five decades and beyond.” - Gary Hustwit

Gary Hustwit is a filmmaker and visual artist based in New York and the CEO of Anamorph, a generative media studio and software company. He has produced over twenty documentaries and film projects, many of which are about music, including subjects such as Wilco (I Am Trying To Break Your Heart), Animal Collective (Oddsac), and Mavis Staples (Mavis!).

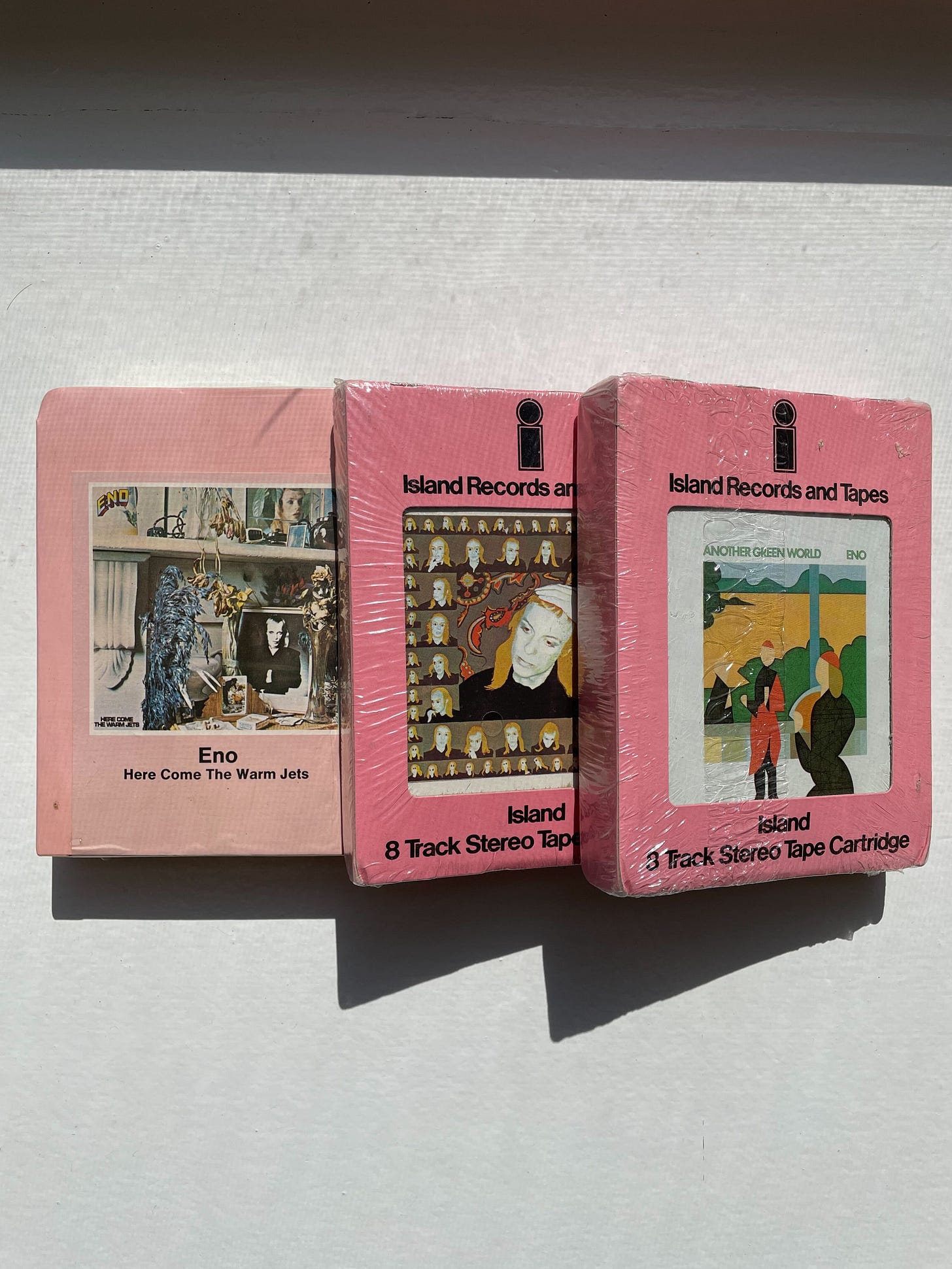

Gary worked with punk label SST Records in the late 1980s, helping release the music of bands like Black Flag, Sonic Youth, and Dinosaur Jr. and later ran the independent book publishing house Incommunicado Press, then started the DVD label Plexifilm in 2001. With Plexifilm, Gary released over 40 films theatrically and on home video [Editor’s note: Look for me with dodgy hair in High Tech Soul, a 2006 Plexifim release].

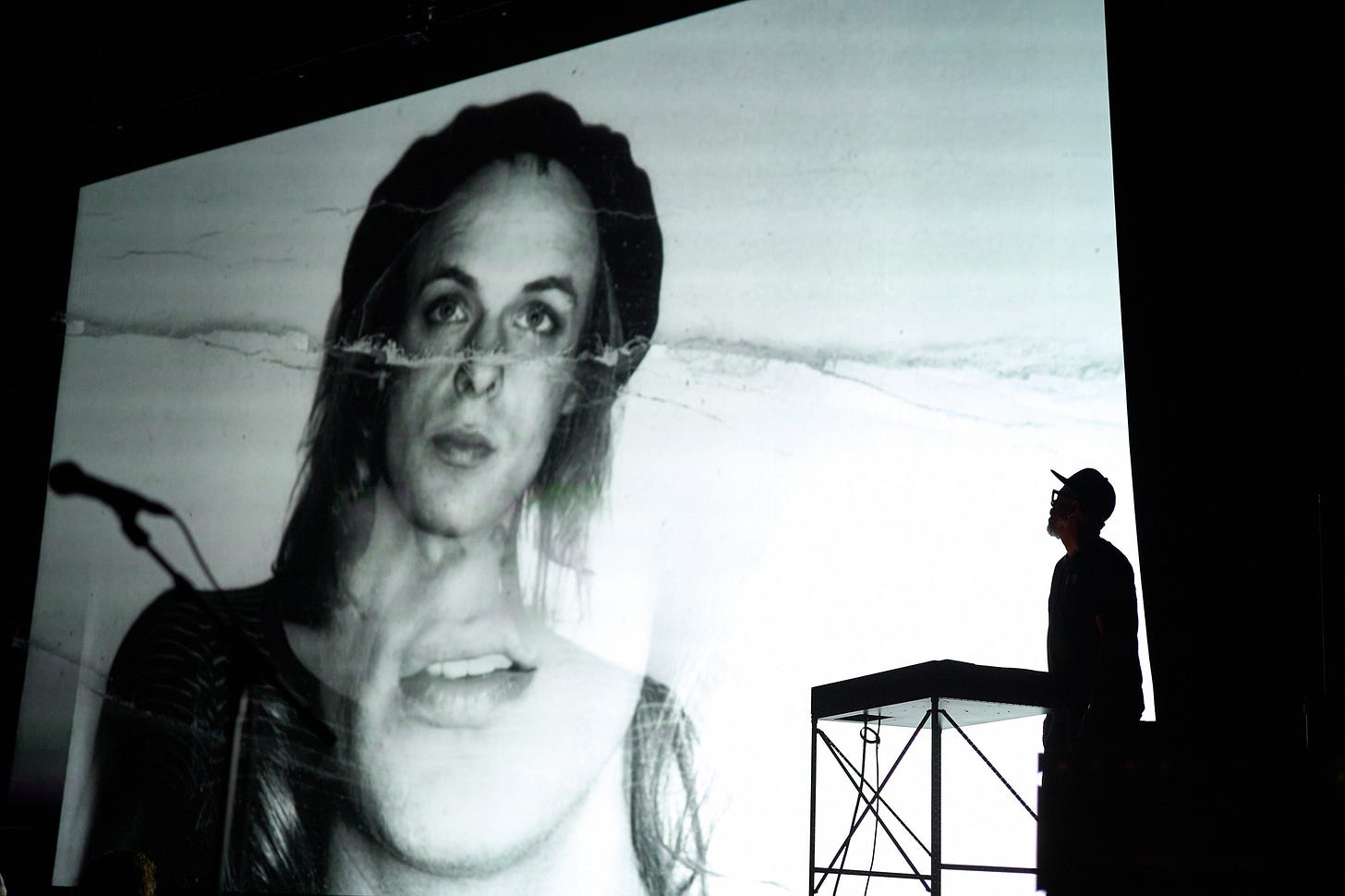

In 2007, around when I met him, he made his directorial debut with Helvetica, the world’s first feature-length documentary about graphic design and typography. He continued to explore how design affects our daily lives with his films Objectified (2009), Urbanized (2011), Workplace (2016), and Rams (2018). His most recent project is Eno, a documentary about, of course, Brian Eno, which uses generative technology in its creation and exhibition. Eno premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival and has been shortlisted for Best Documentary Feature at the 97th Academy Awards. It is the first documentary in which no two viewings are identical, drawing from 500+ hours of footage, which will only expand with time. The version I saw contained Eno talking about tie-dying shirts and saying no to producing Joni Mitchell (a regret). My friends saw entirely other footage. No one was let down.

I encourage you (Gary didn’t ask me) to buy a ticket for this Friday’s first “streaming” version of this documentary: 24 Hours of "Eno" Livestream at a price of ~$20 that will be easily recouped with renewed thinking about your own life and creativity.

I first met Gary in the mid-2000s when he was running Plexifilm, which was becoming the “A24” of docs at the time. Plexifilm released seminal works that were vital to the culture in a pre-streaming era. We would trade records and merch for DVDs when I would visit him at Greenpoint’s pencil factory building (which Ghostly would move into later). It was the beginning of a long camaraderie. The last time I saw Gary was at Vidiots last summer in LA, where he was exhibiting Eno, a remarkable document, not only because of its subject but because of its approach, another example of how artists can use new tools (AI) to make something creative, and not as many fear, a race to the bottom.

Gary is remarkably consistent in demeanor and appearance. He is a calming presence, which is probably why guarded individuals trust him to tell their stories. Besides the work itself, my main inspiration from Gary is his top-to-bottom hard work with each release. In an interview from a podcast last year, Gary mentioned how he sees the whole process, from creating a film to marketing and exhibition to even merch, as part of “filmmaking,” a trait that probably comes from his music roots. Gary has always been great at visually creating a space around his films (yes, like an album), and each touchpoint feels personal.

What’s exciting about Eno and the generative filmmaking platform he is creating is that it is groundbreaking and renews the possibility of film re-watching. If the filmmaker desires to (most importantly), they could add new interviews or remove them, making them “living” films. There’s a fear here that artists will meddle with classics (the great Greedo debate for Star Wars fans of yore), but this presumes the worst, and I tend to trust most artists to make good choices. I personally would rewatch 1983’s graffiti epic, Style Wars (another great Plexifilm DVD), even more than annually if I knew Henry Chalfant could still meddle with it, adding found footage, strengthing other characters, or even adding to the timeline.

Around the time I met Gary, my friend

(who made a great Herb mix) was helping me understand the film space better, both helping us make small docs for Ghostly and allowing me to “assist” when they went to shoot the TED conference in 2010. It was in those rooms that I understood documentaries were not just the chronicling of nature, but active storytelling and editing were needed before the shoot, which blew my mind. You had to be supernaturally ahead of the story to capture the story.I was also immensely moved by the work of the late Hillman Curtis, whose mini-doc on Eno and David Byrne inspired me to launch our own design series capturing artists we worked with within their natural environments.

Eno is an artist whose repute only gains momentum as he has touched almost every major theme in music culture in his career. Besides the coining of ‘ambient,’ of course, he’s been an early predictor of almost every major movement in music, from electronically-enhanced production and sampling (My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts), generative ideas/AI (Bloom app and the Oblique Strategies cards), mixed media and art/music (Music For Installations), curation (the Obscure label), collaboration (nearly all of his early albums), while simultaneously charting a new sort of artist entrepreneurialism, helping torque up some of the biggest bands of all time with his production (U2, Coldplay, Talking Heads).

Eno's popularity in this millennium is due to his representation of an amateur perspective on art, which makes it conceptually accessible to non-musicians, even designers. As an excellent communicator, he has routinely shared his methods, similar to today's social media, presenting his work as an open lab readily available to everyone.

You also can’t talk film this week without mentioning David Lynch, and much has been said about how Lynch is one of the most influential filmmakers on music culture; I think the same could be said for Eno for film in some ways. Eno, more than one major sound or musical cue, represents an ideal mood state to reveal a complex feeling, a complex, vaguely melancholy depth to a scene. For something to be Eno-esque, we accept it is expansive, vaguely spiritual, alien, but homey, all at once. It’s a rare feat. His stuff is in more films than I even realized, but it's the blue tint of his work in Heat (1995) that I think about more often than any other film/music combo.

Me, On Eno

My ultimate Eno playback so far was Ambient 1 on a Sony Sports Discman on an overnight Amtrak bound from Ann Arbor to Kansas City, chasing a girl many years ago. Much like Simon Reynolds (Herb 32) reports below, while listening to Kraftwerk on the Autobahn, it was the body in motion, the whirring landscape, and the joy and sadness that accumulated that led me to tears.

That is when I was travelling in a car on the actual Autobahn, somewhere between the Black Forest and Cologne, about a dozen years ago. Like many men, crying doesn't come easy: personal tragedy or torment is less likely to produce a torrent than particular pieces of music, certain films. As the pastures rolled by the passenger window, the lush scenery punctuated by gently gyrating electrical windmills, the motorik CD of Neu!, La Dusseldorf and Kraftwerk I'd prepared for this moment reached one of the latter's peak tunes. It might have been "Trans-Europe Express," or "Neon Lights," or "Autobahn" itself — I had to turn my face away and look fixedly out of the window to hide my tears. I'm not sure why the music, so free of anguish and turmoil, has this paradoxical effect. Partly it's a response to the grandeur of its ambition, the achieved scope of the Kraftwerk project. But it's also to do with what Lester Bangs called the "intricate balm" supplied by the music itself: calming, cleansing, gliding along placidly yet propulsively, it's a twinkling and kindly picture of heaven.

The cover and music of Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978) depict a topography or a scarred landscape, like a brain, which captures both the science and mystery of being alive. Eno's ideas have remained because they still represent the challenges of contemporary life, a curious philosophical bent, and a vague spirituality. Kraftwerk, another favorite and one of the most influential artists or groups of the present day, approaches this from the other side.

Released only a month apart in 1978, The Man Machine and Ambient 1 albums contemplate a life interwoven with technology, made by people who saw themselves not as “muscians” but something closer to Kraftwerk’s “music workers” concept. Eno’s studio is a tabletop set up with voices and players not present, a tape loop seance summoning music made from the past for the future. Kraftwerk’s vaguely more rock-ist approach to being a band (a self-manufactured robot boy band, at that) still depicts the studio as the final destination for music, “Spacelab” as both the creative hub and the receptor of said sounds.

While Man Machine is a Furutist ode about the rational dignity of machine-age living, an ideal, Airports is more about life as it is, with the airport as a metaphor or containers for humans in passing, a stasis between phases, between life and death, coming and going. Kraftwerk’s technical idealism would give way to 1981's Computer World, their most prescient album, representing a power schism between humans and computers, or a tug of war between the individual might ("Home Computer") and vague dissatisfaction (+ subsequent goonerism) ("Computer Love") that would drive the individual further into the machine age void.

It’s easy to forget that Airports isn’t just tapes and synths but unembodied voices. "1/2,” my favorite of the set, is a ghostly chorus. In my viewing of Eno, his love of choirs and acapella music was highlighted; it’s an aspect of his practice that is overlooked: the human heart. The way Airports rise and falls feels like a breath, just like the autonomous drift Kraftwerk’s train-like glide. Both are ideals of sorts.

In this regard, Eno is post-human, more of a set of standards, morals, ideals, and practices that will outlive his time on earth. Eno, like Hustwit, is more of a technician, and his fingerprints remain sort of elusive amidst all the fanfare. I would guess this is part of the instinct that guides Hustwit, and part of what I love about his films. They are somehow able to get out of the way of it all. Hustwit doesn't take up a lot of air with his subjects, nor is he seeking a resolution. Technology, aided by story and taste, is used as a means for human understanding and to survey the passing of time. The beauty of life is held as a transient, flickering thing, each moment as meaningful or meaningless as you decide.

Having followed both you and Gary Hustwit across various social media websites and newsletters for going on two decades, I’m getting a big “all my friends are friends” vibe from this ❤️

Wow. this is so good.