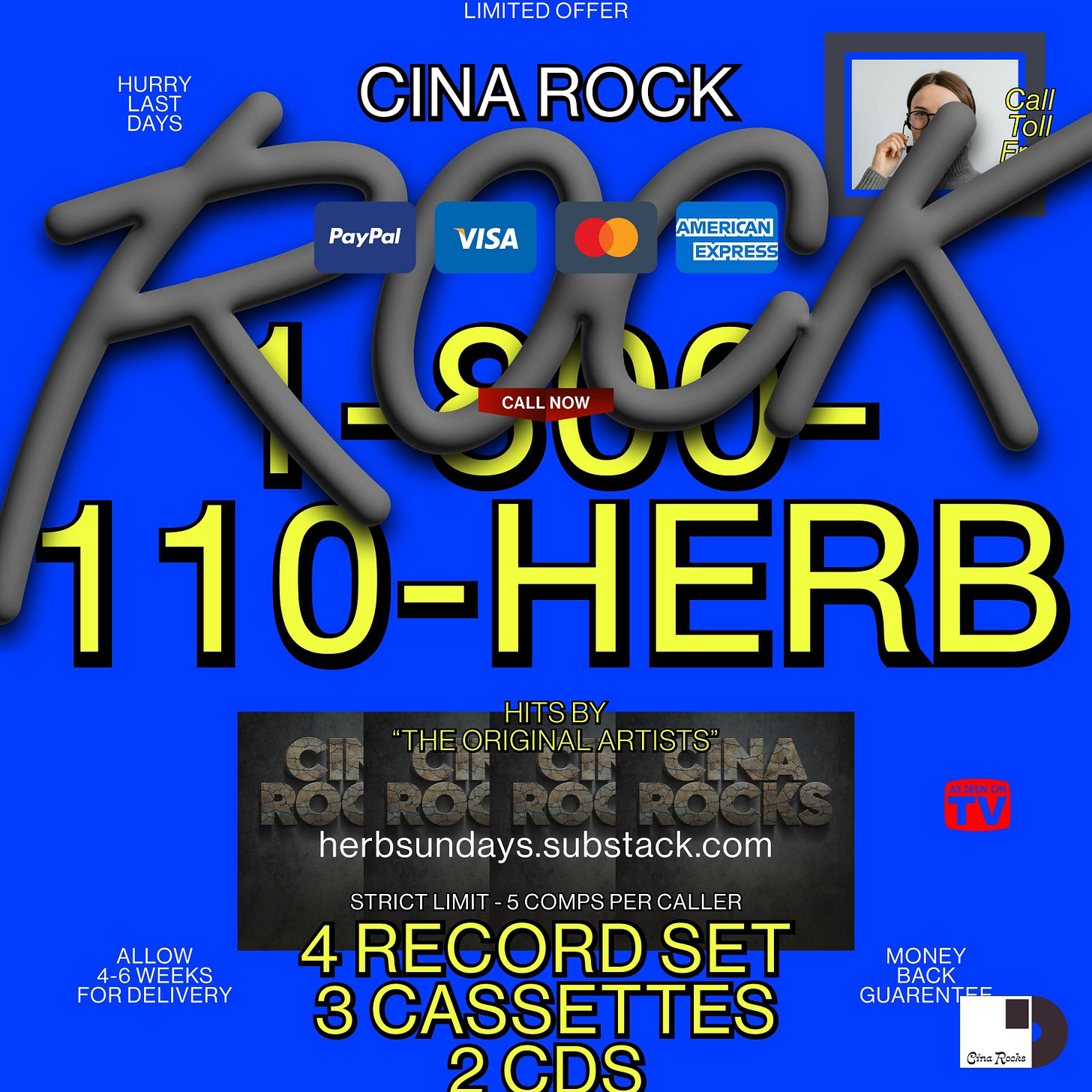

Herb Sundays 110: Michael Cina (Apple, Spotify). Art by Cina.

“My journey into the world of music started before I was even born. My first concert was Bloodrock/Grand Funk Railroad, I was in my mom’s stomach, kicking the entire time. They said it was easily the loudest concert they had been to. Out of the womb I grew up with a steady diet of psych and hard rock, my father’s favorite genres at the time. Weekends often meant hitting the record store with him, barely tall enough to glimpse the LPs on the shelves. At the age of 7, I started my own record collection, my taste was somewhere between Kiss and the Village People, to my dad’s dismay.

This mixtape is a tribute to my father, who passed on his love for music and passion for deeply listening. The playlist echoes the bands that provided the soundtrack to my childhood. Each song on this mix holds a story, a memory, a piece of my past. Like the copy of The Cyrkle LP that my mom gifted to my dad in the late '60s, a relic of their dating days. Most of the albums on this mix are now woven into my collection with my additions. Music isn't just about the art; it's about the connections and the moments it creates, tying us to our past and guiding us into the future.” - Michael Cina

Since this is a newsletter about playlists, we need to cover their history a bit too. I got hung up on ‘Greatest Hits’ recently. I'm not sure where this is leading, but it’s fun.

When Mike Cina and I were talking about what his next Herb installment would be, I looked through his public playlists and was struck by “Cina Rock” as a title. With how my mind works, full of detritus from years of culture damage, I quickly grasped 1987’s Freedom Rock, a TV commercial-aided compilation that I’ve never owned or even seen in person but whose advert played regularly when I was a kid. Freedom Rock is a mishmash of Southern Rock, Philly Sound, Soft Rock, and more. It doesn’t represent American music (as the cover suggests) only either; it is just an idea loosely held together by an ad.

The infomercial compilation era, or TV comp genre, as we’ll call it, includes other titles such as Pure Moods (1994), a New Age/electronic adjacent comp (again, an imaginary scene) that has gotten a critical reevaluation in recent years (pick up a Dirt subscription). Some of this interest may be due to a reassessment of Enya as an artist, and some of it is just ‘90s nostalgia, but there is something comforting in running it back. From Mina Tavakoli’s 2020 Pitchfork Sunday Review:

You may not remember hearing this work, but after watching the commercial, you might find yourself feeling that you’ve always known lines from its script. Swooning and naked in its pride, the 17-song compilation album, advertised in 60-second hallucinations disguised as infomercials, was a warm vat of music that we might today refer to loosely as “new age.” Its carefully selected tracklist—a mosaic made largely up of film or television scores, or trance remixes thereof—seemed engineered to induce a ridiculous sort of fugue state. For some, hearing the album might pang a Proustian memory of falling asleep on a familiar sofa. For others, it can suggest an intensely ambivalent mixture of pity and allure. Pure Moods’ essence is safe, formless, and mostly meaningless, like a piece of art hung in a bathroom. For me, and for many others, it felt like paradise.

Dirt also unearthed this gem from the NY Daily News in 1997

“a kind of marketing plan scammed into a genre. The “style” began when savvy industry types combed their back catalogues to find enough pre-existing compositions which fit the above description to fabricate a firmly defined sound.

Virgin Records put together the first “pure moods” compilation, establishing a link between warmed-over hits by Enya, Enigma, Deep Forrest and Angelo Badalamenti. To flesh out this budding genre, the LP trolled back to Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” (from ’74) and Jean Michel Jarre’s “Oxygene” (from ’77).

More than just a sound ties these pieces together. The music also exudes a quasi-“spiritual” quality that promises to bestow a sense of virtue just by listening.

These compilations weren’t invented in the ‘80s/’90s. There have been "As seen on TV"compilations for ages, pioneered by companies like Canada’s K-tel (you'd recognize those LPs at any Goodwill shop) since the ‘60s (there’s a doc on YouTube I need to watch) which helped pioneer direct marketing. The most successful brand of this ilk is likely the Now That’s What I Call Music series, which has been going since the early ‘80s and, according to Wiki, has been selling at least RIAA Silver up until 2022. Obviously, streaming has taken a piece of these sales, but the brand marches on, now in edition 117 and even on vinyl.

The Herb 110 Cina Rocks comp is, of course, great cause Michael has a terrific ear, but it also deals in the unexpected, some hits and some album tracks, with a powder keg of dopamine around each corner. It’s an atlas of Cina’s life, the only connection is emotion, which hangs together. If I had more focus/time, I would have tried to commission the comedian who regularly serves up breathless lip-syncs of these ads.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Listening to some of these comps again, as fans have made replica playlists on DSPs, the thing I like is their looseness with genre. The overreaching shape forms an archipelago of taste, a false history as it were. Freedom Rock is apparently a Vietnam era reverie, that merges music has broad as The O’ Jays and Skynrd. It’s influence isn’t that suprising. TV time, especially with repeat airings, is hugely valuable, especially then with less channels and less internet.

The joy of the ads was also in recognizing the songs, and predicting them. In some ways these comps predict the direction that DSP playlists are going, less genre and more mood/feeeling. The songs would slide by in 5 second chunks almost like the TikToks of their day, burning in a micro-impression of these earworms for sleepless viewers, no chance to fast forward in sight. Even if you were making fun of these ads, you were absorbing them. You also probably weren’t gonna hear this music on TV or radio, so it remained an intro to another world, another lifestyle even.